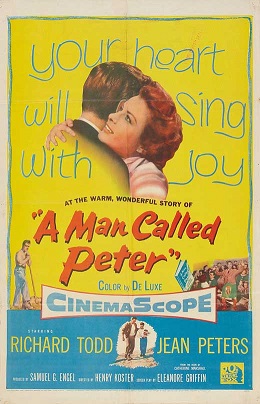

The film’s tagline reads, “Your heart will sing with joy” and that about sums up A Man Called Peter.

The film’s tagline reads, “Your heart will sing with joy” and that about sums up A Man Called Peter.

Henry Koster was the director behind such underrated gems as The Bishop’s Wife and Harvey, and although this film is starkly more realistic, it shares the same unabashed earnestness of its predecessors. Its tone is similarly reverent of its subject matter, the story of the man Peter Marshall (Richard Todd), but that’s hardly a point of derision because its sincerity feels well-founded.

The narrative cycles through his changing life and times from his childhood days as a rebellious boy in Scotland to the defining moment when he truly resolved to follow God’s plan in his life. Following his days in seminary, he goes on to two parishes in Covington and Atlanta, Georgia. One church flourishes from humble beginnings and the latter, while boasting a large congregation is weighed down by apathy and financial problems.

It is there where Peter Marshall’s impassioned sermons begin to breathe life into the dead bones in the pews, leading people from near and far to take heed of his words. Like any charismatic speaker like a Dr. King or even a John Knox, his words are rich and passionate. To use a film term, the sermons become stirring monologues from the pulpit delivered unbelievably convincingly by Richard Todd.

He talks emphatically about the rationality of the Gospel and the idea of relying on a certain amount of faith. He elucidates the character of the real Christ of the Gospels with tremendous vigor. He muses on human love and what that means for him and others — most of the young ladies present listen with baited breath.

One such admirer and a longtime faithful parishioner is the young college gal Catherine Wood (Jean Peters), and it is no wonder she falls for him. However, initially, her love for him is not so much unrequited as it is unknown. That is until the day she comes to meet her hero face to face. Their love story is equal measures tearful and romantically splendorous as they come together, pursuing what they truly perceive to be God’s will.

And they lead a humble albeit happy life before Peter makes the biggest transition of his pastoral career, moving congregations to a historical relic of a church which formerly had presidents in attendance. Now it’s a building half full of old hypocrites and a handful of apathetic souls, but once more Reverend Marshall comes with a fervency in his sermons, while still exhibiting an underlying graciousness. For lack of a better word, he drops truth bombs. Some people aren’t ready to hear, but many are.

What follows is a radical religious revival throughout Washington D.C. His congregation becomes a young people’s church and a welcoming haven for governmental officials still kicking the tires of religious faith. But Peter Marshall welcomes all in and in turn has an exponential impact on not only his community but the very fabric of this nation. He becomes trusted counsel to Congressmen, plays ball with local children and helps set up a local canteen for outgoing soldiers.

By anyone’s standards, it seems like Peter and his faithful Catherine have done so much good. But as often happens, tragedy hits their humble family with a vengeance. Catherine is stricken with tuberculosis which keeps her bedridden for many months. But together they get through it and she recovers, only to have Peter be offered a position as the chaplain of the Senate. However, once more, bad things happen to good people and Peter suffers a coronary thrombosis. Only days later he’s dead and it truly feels that only the good die young.

It simply does not make sense, but if we look at Peter Marshall himself for guidance, he gives us a roadmap of how we can try and cope. Even when his wife is sick, he encourages her that God does not trade retribution with us. It’s not like all the weight of our past misdeeds are stacked up against us. Still, he cries out to his God with the illness of his wife like the psalmists of old. He doesn’t have to be content with suffering, and he’s not, but he’s also fearless in his own life. He lives with almost reckless abandon, because of a certain confidence in his faith.

For some, this religious biopic will be admittedly pious and slogging but there’s a surprising richness to Marshall’s story, embodied quite excellently by Richard Todd. Its colored frames are rich equally matched by Marshall’s own mellifluous brogue and personable humanity. Jean Peters subverts my expectations once again with heartfelt depth. It’s a film made in an age when shot lengths could linger, allowing us to ride the waves of a single performance or a bit of dialogue. But most astonishing of all, it’s quite easy to draw parallels to now, because as it happens, there’s nothing that new under the sun.

It should make us beg the question, what if pastors and their churches were living out these kinds of lives? Genuinely loving other people well and dramatically impacting the communities around them — in a sense breathing new life into tired and weary people. If Peter Marshall is any indication, there’s a possibility for dynamic change. Reverend Marshall passed away at the age of 46, but it’s easy to conclude that his was a life well-lived. If only we were all so lucky. Thankfully there’s still time.

3.5/5 Stars